50 nejlepších filmů všech dob pro rok 2012 podle časopisu Sight&Sound

The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time

846 critics, programmers, academics and distributors have voted – and the 50-year reign of Kane is over. Our critics’ poll has a new number one.

Introduction

Ian Christie rings in the changes in our biggest-ever poll.

And the loser is – Citizen Kane. After 50 years at the top of the Sight & Sound poll, Orson Welles’s debut film has been convincingly ousted by Alfred Hitchcock’s 45th feature Vertigo – and by a whopping 34 votes, compared with the mere five that separated them a decade ago. So what does it mean? Given that Kane actually clocked over three times as many votes this year as it did last time, it hasn’t exactly been snubbed by the vastly larger number of voters taking part in this new poll, which has spread its net far wider than any of its six predecessors.

But it does mean that Hitchcock, who only entered the top ten in 1982 (two years after his death), has risen steadily in esteem over the course of 30 years, with Vertigo climbing from seventh place, to fourth in 1992, second in 2002 and now first, to make him the Old Master. Welles, uniquely, had two films (The Magnificent Ambersons as well as Kane) in the list in 1972 and 1982, but now Ambersons has slipped to 81st place in the top 100.

So does 2012 – the first poll to be conducted since the internet became almost certainly the main channel of communication about films – mark a revolution in taste, such as happened in 1962? Back then a brand-new film, Antonioni’s L’avventura, vaulted into second place. If there was going to be an equivalent today, it might have been Malick’s The Tree of Life, which only polled one vote less than the last title in the top 100. In fact the highest film from the new century is Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, just 12 years old, now sharing joint 24th slot with Dreyer’s venerable Ordet…

Ian Christie’s full essay on changing fashions on our new poll is published in the September 2012 issue of Sight & Sound, available from 3 August on UK newsstands and as a digital edition from 7 August. See Nick James’s poll coverage introduction for details of our methodology. Texts below are quotations from our poll entries and magazine coverage of the top ten. Links are to the BFI’s Explore Film section. The full, interactive poll of 846 critics’ top-ten lists will be available online from 15 August, and the Directors’ poll (of 358 entries) a week later.

THE TOP 50

1. Vertigo

Alfred Hitchcock, 1958 (191 votes)

Hitchcock’s supreme and most mysterious piece (as cinema and as an emblem of the art). Paranoia and obsession have never looked better—Marco Müller

After half a century of monopolising the top spot, Citizen Kane was beginning to look smugly inviolable. Call it Schadenfreude, but let’s rejoice that this now conventional and ritualised symbol of ‘the greatest’ has finally been taken down a peg. The accession of Vertigo is hardly in the nature of a coup d’état. Tying for 11th place in 1972, Hitchcock’s masterpiece steadily inched up the poll over the next three decades, and by 2002 was clearly the heir apparent. Still, even ardent Wellesians should feel gratified at the modest revolution – if only for the proof that film canons (and the versions of history they legitimate) are not completely fossilised.

There may be no larger significance in the bare fact that a couple of films made in California 17 years apart have traded numerical rankings on a whimsically impressionistic list. Yet the human urge to interpret chance phenomena will not be denied, and Vertigo is a crafty, duplicitous machine for spinning meaning…—Peter Matthews’ opening to his new essay on Vertigo in our September issue

2. Citizen Kane

Orson Welles, 1941 (157 votes)

Kane and Vertigo don’t top the chart by divine right. But those two films are just still the best at doing what great cinema ought to do: extending the everyday into the visionary—Nigel Andrews

In the last decade I’ve watched this first feature many times, and each time, it reveals new treasures. Clearly, no single film is the greatest ever made. But if there were one, for me Kane would now be the strongest contender, bar none—Geoff Andrew

All celluloid life is present in Citizen Kane; seeing it for the first or umpteenth time remains a revelation—Trevor Johnston

3. Tokyo Story

Ozu Yasujiro, 1953 (107 votes)

Ozu used to liken himself to a “tofu-maker”, in reference to the way his films – at least the post-war ones – were all variations on a small number of themes. So why is it Tokyo Story that is acclaimed by most as his masterpiece? DVD releases have made available such prewar films as I Was Born, But…, and yet the Ozu vote has not been split, and Tokyo Story has actually climbed two places since 2002. It may simply be that in Tokyo Story this most Japanese tofu-maker refined his art to the point of perfection, and crafted a truly universal film about family, time and loss—James Bell

4. La Règle du jeu

Jean Renoir, 1939 (100 votes)

Only Renoir has managed to express on film the most elevated notion of naturalism, examining this world from a perspective that is dark, cruel but objective, before going on to achieve the serenity of the work of his old age. With him, one has no qualms about using superlatives: La Règle du jeu is quite simply the greatest French film by the greatest of French directors—Olivier Père

5. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

FW Murnau, 1927 (93 votes)

When F.W. Murnau left Germany for America in 1926, did cinema foresee what was coming? Did it sense that change was around the corner – that now was the time to fill up on fantasy, delirium and spectacle before talking actors wrenched the artform closer to reality? Many things make this film more than just a morality tale about temptation and lust, a fable about a young husband so crazy with desire for a city girl that he contemplates drowning his wife, an elemental but sweet story of a husband and wife rediscovering their love for each other. Sunrise was an example – perhaps never again repeated on the same scale – of unfettered imagination and the clout of the studio system working together rather than at cross purposes—Isabel Stevens

6. 2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick, 1968 (90 votes)

2001: A Space Odyssey is a stand-along monument, a great visionary leap, unsurpassed in its vision of man and the universe. It was a statement that came at a time which now looks something like the peak of humanity’s technological optimism—Roger Ebert

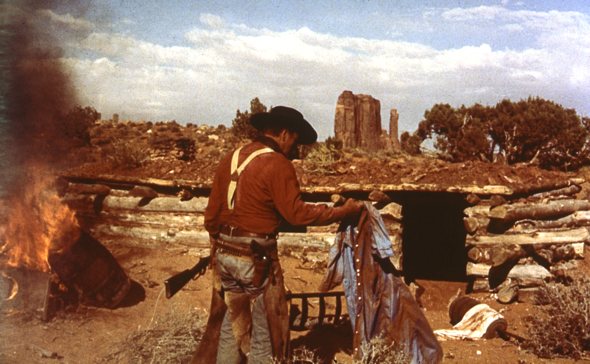

7. The Searchers

John Ford, 1956 (78 votes)

Do the fluctuations in popularity of John Ford’s intimate revenge epic – no appearance in either critics’ or directors’ top tens in 2002, but fifth in the 1992 critics’ poll – reflect the shifts in popularity of the western? It could be a case of this being a western for people who don’t much care for them, but I suspect it’s more to do with John Ford’s stock having risen higher than ever this past decade and the citing of his influence in the unlikeliest of places in recent cinema—Kieron Corless

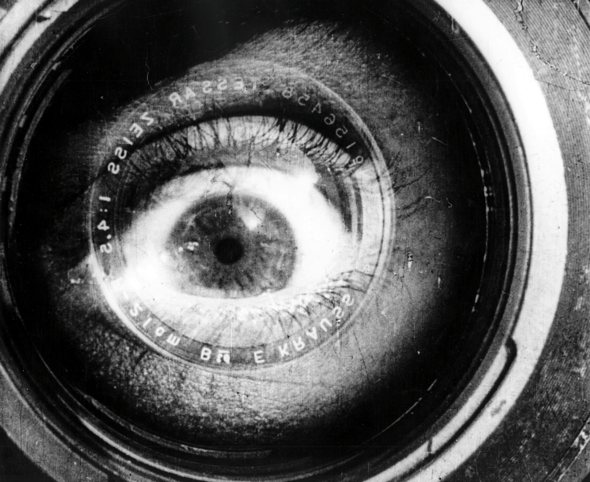

8. Man with a Movie Camera

Dziga Vertov, 1929 (68 votes)

Is Dziga Vertov’s cine-city symphony a film whose time has finally come? Ranked only no. 27 in our last critics’ poll, it now displaces Eisenstein’s erstwhile perennial Battleship Potemkin as the Constructivist Soviet silent of choice. Like Eisenstein’s warhorse, it’s an agit-experiment that sees montage as the means to a revolutionary consciousness; but rather than proceeding through fable and illusion, it’s explicitly engaged both with recording the modern urban everyday (which makes it the top documentary in our poll) and with its representation back to its participant-subjects (thus the top meta-movie)—Nick Bradshaw

9. The Passion of Joan of Arc

Carl Dreyer, 1927 (65 votes)

Joan was and remains an unassailable giant of early cinema, a transcendental film comprising tears, fire and madness that relies on extreme close-ups of the human face. Over the years it has often been a difficult film to see, but even during its lost years Joan has remained embedded in the critical consciousness, thanks to the strength of its early reception, the striking stills that appeared in film books, its presence in Godard’s Vivre sa vie and recently a series of unforgettable live screenings. In 2010 it was designated the most influential film of all time in the Toronto International Film Festival’s ‘Essential 100’ list, where Jonathan Rosenbaum described it as “the pinnacle of silent cinema – and perhaps of the cinema itself”—Jane Giles

10. 8½

Federico Fellini, 1963 (64 votes)

Arguably the film that most accurately captures the agonies of creativity and the circus that surrounds filmmaking, equal parts narcissistic, self-deprecating, bitter, nostalgic, warm, critical and funny. Dreams, nightmares, reality and memories coexist within the same time-frame; the viewer sees Guido’s world not as it is, but more ‘realistically’ as he experiences it, inserting the film in a lineage that stretches from the Surrealists to David Lynch

—Mar Diestro Dópido

—Mar Diestro Dópido

11. Battleship Potemkin

Sergei Eisenstein, 1925 (63 votes)

12. L’Atalante

Jean Vigo, 1934 (58 votes)

13. Breathless

Jean-Luc Godard, 1960 (57 votes)

14. Apocalypse Now

Francis Ford Coppola, 1979 (53 votes)

15. Late Spring

Ozu Yasujiro, 1949 (50 votes)

16. Au hasard Balthazar

Robert Bresson, 1966 (49 votes)

17= Seven Samurai

Kurosawa Akira, 1954 (48 votes)

17= Persona

Ingmar Bergman, 1966 (48 votes)

19. Mirror

Andrei Tarkovsky, 1974 (47 votes)

20. Singin’ in the Rain

Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly, 1951 (46 votes)

21= L’avventura

Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960 (43 votes)

21= Le Mépris

Jean-Luc Godard, 1963 (43 votes)

21= The Godfather

Francis Ford Coppola, 1972 (43 votes)

24= Ordet

Carl Dreyer, 1955 (42 votes)

24= In the Mood for Love

Wong Kar-Wai, 2000 (42 votes)

26= Rashomon

Kurosawa Akira, 1950 (41 votes)

26= Andrei Rublev

Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966 (41 votes)

28. Mulholland Dr.

David Lynch, 2001 (40 votes)

29= Stalker

Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979 (39 votes)

29= Shoah

Claude Lanzmann, 1985 (39 votes)

31= The Godfather Part II

Francis Ford Coppola, 1974 (38 votes)

31= Taxi Driver

Martin Scorsese, 1976 (38 votes)

33. Bicycle Thieves

Vittoria De Sica, 1948 (37 votes)

34. The General

Buster Keaton & Clyde Bruckman, 1926 (35 votes)

35= Metropolis

Fritz Lang, 1927 (34 votes)

35= Psycho

Alfred Hitchcock, 1960 (34 votes)

35= Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles

Chantal Akerman, 1975 (34 votes)

35= Sátántangó

Béla Tarr, 1994 (34 votes)

39= The 400 Blows

François Truffaut, 1959 (33 votes)

39= La dolce vita

Federico Fellini, 1960 (33 votes)

41. Journey to Italy

Roberto Rossellini, 1954 (32 votes)

42= Pather Panchali

Satyajit Ray, 1955 (31 votes)

42= Some Like It Hot

Billy Wilder, 1959 (31 votes)

42= Gertrud

Carl Dreyer, 1964 (31 votes)

42= Pierrot le fou

Jean-Luc Godard, 1965 (31 votes)

42= Play Time

Jacques Tati, 1967 (31 votes)

42= Close-Up

Abbas Kiarostami, 1990 (31 votes)

48= The Battle of Algiers

Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966 (30 votes)

48= Histoire(s) du cinéma

Jean-Luc Godard, 1998 (30 votes)

50= City Lights

Charlie Chaplin, 1931 (29 votes)

50= Ugetsu monogatari

Mizoguchi Kenji, 1953 (29 votes)

50= La Jetée

Chris Marker, 1962 (29 votes)

Komentáře